We may have found New Jersey's first legitimate road tripper, and she was a woman with moxie.

Hackensack-born Alice Huyler Ramsey was probably among the first people to get her driver's license in New Jersey, and an unlikely motorist for the early 1900s. She'd dropped out of Vassar College to marry a considerably older attorney, John R. Ramsey, and was the mother of a two year old boy. According to most accounts, her husband encouraged her to learn to drive after the horse pulling her carriage was spooked by a passing car. It's quite possible she would have come up with the idea on her own: her father had supported her childhood interest in machinery, and as events would prove, she was up for a good challenge.

|

Alice Huyler Ramsey and her Maxwell.

Note the New Jersey plates. |

Alice took to driving like a fish to water. After two lessons, she'd mastered the automobile and was on the road, logging thousands of miles tooling around Bergen County. She was so enthusiastic about driving, in fact, that she entered a 200-mile endurance drive to Montauk, Long Island. After the contest, she was approached by the Maxwell-Briscoe automobile company, which saw promotional opportunities in the 22 year old. How many customers could they attract if they could prove that anyone -- 'even a woman' - could drive cross country in a Maxwell car?

Alice was game. After receiving permission from her husband, she left from Maxwell's New York City dealership on June 9, 1909, with the slogan "From Hell Gate to the Golden Gate." She was accompanied by her two older sisters-in-law and a younger female friend, none of whom could drive (apparently road trippers hadn't yet enacted the longstanding rule of always having a relief driver). Heading north into New York State first to make some promotional stops for Maxwell, they then drove west along Lake Erie and then westward, roughly along the combined paths of Interstates 90 and 80.

To appreciate the magnitude of the challenge, consider what we take for granted when we drive our interstates long distances, and take all of it away. There were no regularly-spaced service stations. Finding a good meal was a chancy venture that might be miles off the beaten path. Lodging was catch-as-catch-can in the days before Holiday Inns and other chain hotels; the concept of the motel or motor lodge was still years from being conceived.

And then there were the roads. No maps were available for cross country navigation. East of the Mississippi River, the group used a series of Blue Books, which offered turn-by turn directions that were often unreliable because landmarks were missing or had been changed. The rest of the way, the roads were much less developed, so the travelers stayed close to the telegraph lines that linked towns and cities.

Of the 3600 miles they drove, just over 150 were paved, which led to a lot of ruts, potholes and mud to be negotiated. The Maxwell's tires were treadless and slim by comparison to today's, and even with tire chains, the Ramsey group often found themselves needing to be towed or pulled out by beasts of burden lent by generous farmers. One would wonder if Alice's local driving -- possibly through the Meadowlands -- had prepared her for the muck and mire she would have to conquer on the dirt roads in the Midwest and West.

On the best roads, the group hit speeds up to 42 miles an hour in the open cockpit car and could travel nearly 200 miles in a day. At the worst, they logged only four miles after a long day navigating the muck and mire. They'd often have to ford bridgeless rivers, sleeping alongside a riverbank at least once in the hopes that the water level would have decreased by the time morning came.

Driving a car in the early 1900s also meant knowing what to do when problems came up -- motorists had to carefully monitor gasoline and handle whatever repairs were needed during frequent breakdowns. Alice skillfully handled the malfunctions herself; it took something as serious as a broken axle for her to seek help.

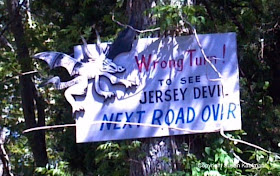

Alice and her group were among the first to get a sense of the majesty of the United States by car. They observed Indians in Nebraska hunting jackrabbits with bow and arrow. They got bedbugs in Wyoming, where they also ran into a posse looking for a murderer. Alice also brought a little of the East Coast west, playing a few impromptu numbers on the piano at a lunchtime restaurant stop in Iowa. And like many travelers yet to come, she enjoyed the reactions Westerners had to her New Jersey license plates. The Maxwell company's publicity brought out curiosity seekers that would meet them along the way

Fifty-nine days after leaving Manhattan, Alice and her crew arrived in San Francisco to a grand celebration. After all that driving, they stayed only three days, taking the train back to New Jersey. Who could blame them? They'd already seen so much, had so many novel experiences. Could San Francisco, as beautiful as it is, even compare?

Nine months after finishing her trek, Alice gave birth to a daughter, but that didn't stop her from having adventures. Over the course of her life, she drove across the country 50 times, the last being in 1975, at the age of 89. The American Automobile Association named her the Woman Motorist of the Century in 1960. She also attempted to drive the six passes of the Swiss Alps but only made it through five, after stopping because her doctor was concerned about her pacemaker.

Alice lived in Hackensack until 1933, when she moved to Ridgewood after her husband's death. She spent the last 30 years of her life in California, where she died in 1983, and is buried in Hackensack. I can't help but wonder why the Turnpike Authority never named a service area after her. After all the miles she put on the odometer, and all the blown tires and steaming radiators she fixed, she deserves memorializing in the domain of pavement, oil and wrenches.