"Ah," I thought as I walked through the door of Old York Books. "This is what college is all about: wandering through tomes and tomes of scholarship and prose." (I was a young and naive English major. Sue me.) I left that day with a set of F. Scott Fitzgerald novels and an intention to return. Sadly, the place closed up shop on Easton and moved to a sketchier part of town, eventually disappearing to points unknown.

Thus, when a friend mentioned the Old Book Shop to Ivan and me a few months ago, my ears perked up. My reading preferences may have changed from fiction to history and American studies, but the lure of the used book store still appealed. Our friend mentioned that the shop specializes in New Jersey history, and he'd found something obscure there, which, of course, drew me to the possibility of finding something similar. We didn't make any solid plans to go, preferring instead to put it into the mental file cabinet for the next time we found ourselves in Morristown.

Conveniently, one of our readers brought the place to mind a few weeks ago by sending me an e-mail about Pinelands-themed books that could add some perspective to our travels. I can always head to the library or scan the internet for data to inform our posts, but there's nothing quite like having source materials right at my fingertips. I've already got my favorites, but there's always room for more. Ivan was more than game for a used book foray; he's made some great finds in the past, including a Civil War recollection by Abner Doubleday that had a contemporaneous news clipping of his obituary pasted inside the back cover. We agreed that we'd make a stop at the shop after our Saturday birding.

|

| Had the Old Book Shop been in business in 1780, Washington, Hamilton and Lafayette definitely would have checked it out after Benedict Arnold's court martial. |

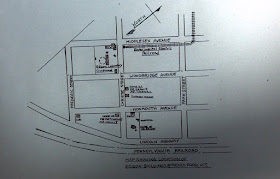

And then, there we were. Blink, and you could have missed it. The shop is in a nondescript brick building along with a bail bonds office, not the usual neighbor for a book store. On an atmospheric level, it's a bit less interesting than the previous location on Spring Street, which was reportedly the site of Benedict Arnold's first court martial.

We walked in to see a very utilitarian environment: rows of books on several aisles of plain shelving, subject matter marked with handwritten labels. The owner was sitting at a table near the door and greeted us as we walked in, but to be honest, I didn't really stop to say hi. Ivan may have, but I went straight for the stacks.

Out of the corner of my eye I noticed that the far wall appeared to be dominated by paperback fiction, but I didn't give it a second look. I was looking for U.S. history and, of course, New Jersey reference books.

First, the history: I was looking specifically for anything that might have been written by or about the staff that worked at Ellis Island during the first half of the 20th century. It's admittedly a niche interest, so I wasn't surprised not to find something, but they did have an impressive selection of presidential biographies and several shelf feet of books on each of the major wars. The range was notable, too, ranging from relatively recently published to over 100 years old.

New Jersey subject matter was easy to find, sitting in a couple of bookcases near the store's front counter. Besides a general state section, books were divided by county, so you could find, for example, the self-published, hardbound history of a particular church in Salem County. That stuff was a little esoteric for my tastes, but I could see where it would be a boon to folks doing very specific research. A typewritten transcript of the diary of Presbyterian missionary John Brainerd might have been helpful when I was researching the story of Indian Mills last December.

Tempted though I was, I showed some degree of restraint and walked out with just four books: a two-volume encomium of Thomas Edison by one of his muckers, Francis Jehl; and two of the classic New Jersey folklore books written by Henry Charlton Beck in the 1930s. Ivan had about the same luck, with books by noted birders Pete Dunne and Sandy Komito. I've gone back since and picked up a second copy of The WPA Guide to 1930s New Jersey to keep in the car.

The Old Book Shop also carries vintage pamphlets, maps, postcards, magazines and advertising posters, as well as legitimately antique leather-bound books. Even if you're not in the market, they're really interesting to check out.

Most remarkable of all, though, are the owners, Chris Wolf and Virginia Faulkner (and you have to love a bookstore owned by someone named Faulkner!). When I returned to check the New Jersey shelves again, we got into a conversation about the WPA Guide which evolved to a discussion of other potential references on the state. It quickly became clear that I could walk in, ask for, say, literature on Andress Floyd and the Self Master Colony, and they would not only know what I was talking about, but could tell me when they'd seen something last. And there's also a good chance this pair would trounce Ivan and me in a game of New Jersey Trivial Pursuit.

As I left, they reminded me that they get new books in every day, so a return trip was in order. That was much was clear, but I'll need to remember my self control, or I'll walk out with half their inventory and a depleted bank account.