Brig. Gen. Zebulon Pike, explorer,

born near here, 1779.

Captured York, Canada,

1813, but killed in attack.

Pike’s Peak named for him.

Yet another western explorer born in New Jersey? You got it. In fact, one of his forebears was the founder of Woodbridge. His father, also named Zebulon, served as an officer under Washington in the Revolutionary War and continued his military service in the newly formed United States Army after independence had been won. As a result, the younger Pike spent most of his youth at forts in what was then the American frontier: Ohio and Illinois. He followed his father's footsteps and joined the army at the age of 15, rising to the rank of first lieutenant by the time he was 20.

While his military responsibilities seemed to focus more on administration and logistics, Pike came of age in the army just as western exploration was coming into vogue. The 1803 acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase nearly doubled the size of the nation, but much of the territory was unknown terrain to all but the natives who lived there. Young Pike was in the perfect place to make an impact, and in 1805, General James Wilkinson, Governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory, appointed him to lead an expeditionary force to find the source of the Mississippi River and bring back influential natives for negotiations. While Pike misidentified the river's origin, the other geographical information he gained was among the first learned for the U.S. government.

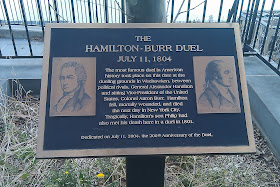

Wilkinson sent Pike on a second expedition in 1806 to locate the sources of the Arkansas and Red Rivers, establish relations with the natives and gain a greater understanding of the region's natural resources. Unlike the Lewis and Clark expedition, this journey started without authorization from President Jefferson and may have even been a spy mission. Some historians conjecture that Wilkinson may have been secretly collecting information for the Spanish government, using Pike as an unknowing accomplice. There's even a school of thought that the general was working in league with Aaron Burr to overtake the western United States, though it's never been proven. (Burr seems such a ready villain to some historians that one wonders if they'd charge him with starting World War I if they could.)

In any case, it was on this second expedition that Pike found the mountain that would eventually bear his name. Arriving in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado in November, lacking sufficient winter clothing and food, he and his team tried to reach the summit of the 14110 foot-high mountain but thought better of it and turned back. He was quoted as claiming that it was likely no man would ever reach the top.

The journey back was a lesson in hardship and disappointment. Pike and his men soldiered on through the winter, some suffering gangrene and frostbite along the way. Captured by Spanish soldiers near Santa Fe, they were interrogated and their records confiscated for a time, but they were generally well treated and eventually set free to return to undisputed U.S. territory.

You'd think that they'd receive warm welcome upon their return, but it wasn't the case. Jefferson himself was more enamored of Lewis and Clark's natural and scientific findings, and rumors had already begun to swirl about Pike's supposed involvement in the Burr conspiracy. Neither he nor anyone on his team received any special consideration for their efforts and hardships endured. If it weren't for Pike's Peak itself, it's doubtful that Zebulon Pike would be anything more than an answer to a particularly tough trivia question.

* Yes, I know that haiku generally take the three line, 5-7-5 syllable format. Go with me on this one.