If you're of a certain age, you might remember Palisades Amusement Park, the entertainment complex that once stood high above the shores of the Hudson River in Cliffside Park and Fort Lee. Between the rides, the pool and the entertainment, it was a big draw for families in the New York metropolitan area until it closed in 1971. Real estate values, it seems, trumped the need for nearby fun, and besides, the host towns appear to have grown weary of the crowds overtaking the park. Municipal officials had hastened the closure by rezoning the property for high-density housing.

Palisades, however, wasn't the first big attraction on the Hudson Cliffs. The Eldorado Amusement Park in Weehawken was a haven for pleasure-seeking visitors starting in 1891, offering a more refined experience. I stumbled upon the story while wandering Boulevard East in search of the site of the Alexander Hamilton-Aaron Burr duel.

Eldorado spanned from the cliffs of the Palisades west to current day Highwood Avenue, bordered by Liberty Place on the North and Duer Place on the South. It lacked the rollercoasters and other rides of more pedestrian parks of the day, preferring to offer more impressive attractions, if the superlative reports of the day are to be believed. Civic leaders, incorporated as the Palisades Amusement and Exhibition Company, built a Moorish themed casino, amphitheater and cliffside castle surrounded by beautifully landscaped gardens. Hungarian impresario Bolossy Kiralfy staged massive shows with casts as large as 1000 performers in the huge music pavilion. A 30 foot fountain on site was said to be the tallest and most expensive structure of its kind in America.

New Yorkers had long been ferrying across the river to flee the hot city summers, and they came to Eldorado in droves. Then, as today, visitors on the shores of the Hudson are greeted by the sight of the massive Palisades, and roads at the time weren't as helpful as they are now in making one's way to the top. An ingenious elevator and train system brought them from ferry slips at the river bank to the park 150 feet above. The marvel was featured in an 1891 issue of Scientific American, sounding very much like a steroid-fed version of the trams we see at amusement parks today.

Information on the park is a bit sketchy, but it seems that a large fire at the casino building in 1898 was the beginning of the end for the Eldorado. Its owners demolished the remaining buildings and sold the property as lots for an exclusive residential subdivision. Proximity to Manhattan was a huge selling point, but fortunately high-rises weren't yet in vogue. Though packed somewhat tightly by suburban standards, the houses that were built on the lots have plenty of character.

Today, the only signs of Eldorado in Weehawken are a historic marker on Boulevard East, and an Eldorado Place. Much like the lost city of gold, it's as if it never existed.

The travels and adventures of a couple of nuts wandering around New Jersey, looking for history, birds and other stuff.

Pages

▼

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

How now, Brown..... University?

Last week's County Road 518 jaunt brought me through Hopewell, a community justifiably proud of its roots. Not only was the town the home of Declaration of Independence signer John Hart, it boasts a lovely old Baptist meeting house and a number of other colonial-era buildings. I wasn't surprised to find a few historical markers in town, but I was thrown for a loop when I read the sign in front of an unadorned white colonial house. Apparently the building had once served as a Baptist parsonage and a school called the Hopewell Academy, from which today's Brown University developed.

So, wait: Brown, the Ivy League school in Providence, Rhode Island, actually started here in New Jersey? Well, it depends on what you mean by 'started.' The university's own website is a bit fuzzy on the school's origin, but other sources state that Brown, like most, if not all of the nine colonial colleges, was conceived by a Protestant sect to foster learning and to train men for the ministry. In this case, it was the Baptist church in Philadelphia that planted the seed, and Reverend James Manning was sent to lead the formation of the school.

Manning himself was a Jerseyman, born in Elizabethtown, raised in Piscataway and educated at the Presbyterian-run College of New Jersey. Before attending the precursor to Princeton University, he prepared for his religious studies at the Hopewell Academy, the first Baptist educational institution of its kind in America.

Manning himself was a Jerseyman, born in Elizabethtown, raised in Piscataway and educated at the Presbyterian-run College of New Jersey. Before attending the precursor to Princeton University, he prepared for his religious studies at the Hopewell Academy, the first Baptist educational institution of its kind in America.

If the impetus for the founding of Brown came from Hopewell and Philadelphia, then why is the school located in Rhode Island? The answer is simple: the colony then known as Rhode Island and the Providence Plantations was home to the first Baptist church in America. The training ground for ministers would be located at the cradle of the faith. Congregationalist ministers were working to establish a school there, as well, so the two groups joined forces to develop what's known as Brown University.

Manning was the first president of the college, also serving as minister of the mother Baptist church in Rhode Island. Later, he was appointed to the Seventh Congress of the Confederation of States, the nation's legislative body before the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Not bad for a Jersey guy, huh?

Manning himself was a Jerseyman, born in Elizabethtown, raised in Piscataway and educated at the Presbyterian-run College of New Jersey. Before attending the precursor to Princeton University, he prepared for his religious studies at the Hopewell Academy, the first Baptist educational institution of its kind in America.

Manning himself was a Jerseyman, born in Elizabethtown, raised in Piscataway and educated at the Presbyterian-run College of New Jersey. Before attending the precursor to Princeton University, he prepared for his religious studies at the Hopewell Academy, the first Baptist educational institution of its kind in America. If the impetus for the founding of Brown came from Hopewell and Philadelphia, then why is the school located in Rhode Island? The answer is simple: the colony then known as Rhode Island and the Providence Plantations was home to the first Baptist church in America. The training ground for ministers would be located at the cradle of the faith. Congregationalist ministers were working to establish a school there, as well, so the two groups joined forces to develop what's known as Brown University.

Manning was the first president of the college, also serving as minister of the mother Baptist church in Rhode Island. Later, he was appointed to the Seventh Congress of the Confederation of States, the nation's legislative body before the ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Not bad for a Jersey guy, huh?

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Where Edison concentrated: iron ore processing at Ogdensburg

A little over a year ago, we made a trip out to Thomas Edison's concrete mile on Route 57 in Stewartsville/New Village, the site of his famed Portland cement factory. What I didn't mention in that account was the earlier use of the equipment that ground stone into fine enough particles to make a durable concrete.

You see, the Wizard of Menlo Park didn't originally set out to make concrete. He was looking to capitalize on the high iron content of the northwestern reaches of New Jersey, to supply concentrated iron ore bricks manufactured from the raw material of Sussex Mountain. And to do it, he built the first Edison, New Jersey: a veritable city of workers and innovative rock crushing machinery that used magnetic force to separate iron from pulverized stone. While mines in western Morris County and beyond were starting to peter out of useful material, he somehow thought that his experience would be different. No matter what, you've got to give the guy credit for optimism.

Finding the Edison mining property wasn't all that easy for me -- this is a trip I took before Ivan and I met, so I didn't have the benefit of his knowledge of the area. After some internet research, I discovered that my target was just off Sussex County Road 620 in Ogdensburg. More specifically, it's on Edison Road. For some reason, the Garmin people hadn't included 620 on their GPS maps, so I was left to do a little automobile bushwacking once I got into the Sussex area.

Finding the Edison mining property wasn't all that easy for me -- this is a trip I took before Ivan and I met, so I didn't have the benefit of his knowledge of the area. After some internet research, I discovered that my target was just off Sussex County Road 620 in Ogdensburg. More specifically, it's on Edison Road. For some reason, the Garmin people hadn't included 620 on their GPS maps, so I was left to do a little automobile bushwacking once I got into the Sussex area.

I arrived to find a stone and brass marker erected by Sussex County not too long ago, and a sign with topographic mapping of several trails that ramble through the woods. Noticing a New Jersey Audubon logo on the topo sign, I realized that I'd come upon one of the organization's unstaffed areas, and that if I'd bothered to look at my Audubon trails guide, I'd have known exactly where to go.

If you check the area out for yourself, be sure to stop at the county marker and check out the photos embedded in it. They show an environment that differs substantially from the woods and open fields currently on the property. More than 500 men and several huge pieces of processing machinery were working furiously during Edison's time there, and there's little to show for it now. Yes, as you walk around, you'll find the remnants of rustic looking stone walls, and a fair number of steel reinforcing rods poking up from the ground, but besides that, there's little to indicate the industry that existed there from 1891 to 1900. Still, though, random rocks on the ground show the telltale reddish-brown shade of oxidized iron. And fittingly, the area is now traversed by a set of high-voltage transmission lines.

If you check the area out for yourself, be sure to stop at the county marker and check out the photos embedded in it. They show an environment that differs substantially from the woods and open fields currently on the property. More than 500 men and several huge pieces of processing machinery were working furiously during Edison's time there, and there's little to show for it now. Yes, as you walk around, you'll find the remnants of rustic looking stone walls, and a fair number of steel reinforcing rods poking up from the ground, but besides that, there's little to indicate the industry that existed there from 1891 to 1900. Still, though, random rocks on the ground show the telltale reddish-brown shade of oxidized iron. And fittingly, the area is now traversed by a set of high-voltage transmission lines.

Edison spent much of his time at Ogdensburg during the eleven years his iron ore business operated, ultimately spending about $2 million of his personal wealth on the unsuccessful venture. Characteristically unaffected by the cost of yet another experiment that didn't work out, he said, "Well, it's all gone, but we had a hell of a good time spending it!"

Where does the cement come in? Like any great inventor and entrepreneur, Edison studied the failed venture to determine lessons learned. He noted that the crushing machinery was especially good at manufacturing finely-ground material that could be used in high-quality cement. The machinery was moved about 45 miles southwest to New Village, and in 1903, a new business was born: Edison Portland Cement. From roads and houses to Yankee Stadium, this durable material showed up all over the place as Edison strived to find markets for the product. Once again, he'd managed to make some pretty tasty lemonade from the lemons he'd been served.

You see, the Wizard of Menlo Park didn't originally set out to make concrete. He was looking to capitalize on the high iron content of the northwestern reaches of New Jersey, to supply concentrated iron ore bricks manufactured from the raw material of Sussex Mountain. And to do it, he built the first Edison, New Jersey: a veritable city of workers and innovative rock crushing machinery that used magnetic force to separate iron from pulverized stone. While mines in western Morris County and beyond were starting to peter out of useful material, he somehow thought that his experience would be different. No matter what, you've got to give the guy credit for optimism.

Finding the Edison mining property wasn't all that easy for me -- this is a trip I took before Ivan and I met, so I didn't have the benefit of his knowledge of the area. After some internet research, I discovered that my target was just off Sussex County Road 620 in Ogdensburg. More specifically, it's on Edison Road. For some reason, the Garmin people hadn't included 620 on their GPS maps, so I was left to do a little automobile bushwacking once I got into the Sussex area.

Finding the Edison mining property wasn't all that easy for me -- this is a trip I took before Ivan and I met, so I didn't have the benefit of his knowledge of the area. After some internet research, I discovered that my target was just off Sussex County Road 620 in Ogdensburg. More specifically, it's on Edison Road. For some reason, the Garmin people hadn't included 620 on their GPS maps, so I was left to do a little automobile bushwacking once I got into the Sussex area.I arrived to find a stone and brass marker erected by Sussex County not too long ago, and a sign with topographic mapping of several trails that ramble through the woods. Noticing a New Jersey Audubon logo on the topo sign, I realized that I'd come upon one of the organization's unstaffed areas, and that if I'd bothered to look at my Audubon trails guide, I'd have known exactly where to go.

If you check the area out for yourself, be sure to stop at the county marker and check out the photos embedded in it. They show an environment that differs substantially from the woods and open fields currently on the property. More than 500 men and several huge pieces of processing machinery were working furiously during Edison's time there, and there's little to show for it now. Yes, as you walk around, you'll find the remnants of rustic looking stone walls, and a fair number of steel reinforcing rods poking up from the ground, but besides that, there's little to indicate the industry that existed there from 1891 to 1900. Still, though, random rocks on the ground show the telltale reddish-brown shade of oxidized iron. And fittingly, the area is now traversed by a set of high-voltage transmission lines.

If you check the area out for yourself, be sure to stop at the county marker and check out the photos embedded in it. They show an environment that differs substantially from the woods and open fields currently on the property. More than 500 men and several huge pieces of processing machinery were working furiously during Edison's time there, and there's little to show for it now. Yes, as you walk around, you'll find the remnants of rustic looking stone walls, and a fair number of steel reinforcing rods poking up from the ground, but besides that, there's little to indicate the industry that existed there from 1891 to 1900. Still, though, random rocks on the ground show the telltale reddish-brown shade of oxidized iron. And fittingly, the area is now traversed by a set of high-voltage transmission lines.Edison spent much of his time at Ogdensburg during the eleven years his iron ore business operated, ultimately spending about $2 million of his personal wealth on the unsuccessful venture. Characteristically unaffected by the cost of yet another experiment that didn't work out, he said, "Well, it's all gone, but we had a hell of a good time spending it!"

Where does the cement come in? Like any great inventor and entrepreneur, Edison studied the failed venture to determine lessons learned. He noted that the crushing machinery was especially good at manufacturing finely-ground material that could be used in high-quality cement. The machinery was moved about 45 miles southwest to New Village, and in 1903, a new business was born: Edison Portland Cement. From roads and houses to Yankee Stadium, this durable material showed up all over the place as Edison strived to find markets for the product. Once again, he'd managed to make some pretty tasty lemonade from the lemons he'd been served.

Thursday, March 22, 2012

Straddling the Jerseys on Province Line Road

Drive around Mercer County near Princeton, and there's a chance you'll come across Province Line Road. Since you'd be comfortably inland from the state boundaries of the Delaware River and the Atlantic Ocean, you'd be excused for wondering how that name came about. The road certainly isn't marking any contemporary boundary, so what's the deal?

I discovered the cause during a recent wandering on County Route 518. Transfixed by the pastoral scenery, I saw the street sign for Province Line and took a turn to see where it would take me. Rounding the corner, I noticed this on my side of the intersection:

To save your eyes a bit of strain, I'll give you the synopsis. When the English took control of the New York/New Jersey area in 1664, the Duke of York gave New Jersey to two lords, Carteret and Berkeley, who probably never even set foot in the New World. The two then designated local representatives to sell portions of their shares to people who actually lived here, who became known as proprietors. (I shared a little of this in an entry about our visit to Perth Amboy last year.)

Look at the map on the plaque, and you'll see a dotted line above Three Bridges. That's where the fun starts. Naturally, when land is conveyed to new owners, boundaries are decided upon, but when it came to East and West Jersey, the process wasn't as simple as a brief discussion over a map. The Duke had divided the east and west provinces with a diagonal line reaching from Little Egg Harbor on the Atlantic to the spot where New Jersey and New York meet on the Delaware River. Sounds easy, right? It would have been, but that border wasn't officially settled until 1769. You can see the problem.

East-west lines were drawn in 1687 and 1719, but the one that stuck was plotted in 1743 by John Lawrence, now marked by Province Line Road near the plaque I found. Nonetheless, the proprietors of continued to squabble over the boundary for another 140 years. These guys really took their jobs seriously, even after their work ceased to have much relevance from a property-deeding perspective. They could learn a lesson from Steve Chernoski, the documentarian who's tackled the mystery of the line between North and South Jersey. Drive around a bit, ask the locals which side they identify with more, and decide by acclaim.

I read a few years ago that a group of surveyors were using GPS instruments to determine the straightness of Lawrence's line. If they drove the same stretch of Province Line Road that I did, they'd be pretty impressed. Check out how straight it is:

I wish I could report that the full length of the road is as pin-straight and travels clear to Little Egg Harbor, but it's not and it doesn't. About a mile away from where I took this photo, I ran into a dead end and had to resort to an intersecting street. Looking at the map when I got home, I discovered the road makes some twists and turns before terminating near a shopping mall.

I discovered the cause during a recent wandering on County Route 518. Transfixed by the pastoral scenery, I saw the street sign for Province Line and took a turn to see where it would take me. Rounding the corner, I noticed this on my side of the intersection:

To save your eyes a bit of strain, I'll give you the synopsis. When the English took control of the New York/New Jersey area in 1664, the Duke of York gave New Jersey to two lords, Carteret and Berkeley, who probably never even set foot in the New World. The two then designated local representatives to sell portions of their shares to people who actually lived here, who became known as proprietors. (I shared a little of this in an entry about our visit to Perth Amboy last year.)

Look at the map on the plaque, and you'll see a dotted line above Three Bridges. That's where the fun starts. Naturally, when land is conveyed to new owners, boundaries are decided upon, but when it came to East and West Jersey, the process wasn't as simple as a brief discussion over a map. The Duke had divided the east and west provinces with a diagonal line reaching from Little Egg Harbor on the Atlantic to the spot where New Jersey and New York meet on the Delaware River. Sounds easy, right? It would have been, but that border wasn't officially settled until 1769. You can see the problem.

East-west lines were drawn in 1687 and 1719, but the one that stuck was plotted in 1743 by John Lawrence, now marked by Province Line Road near the plaque I found. Nonetheless, the proprietors of continued to squabble over the boundary for another 140 years. These guys really took their jobs seriously, even after their work ceased to have much relevance from a property-deeding perspective. They could learn a lesson from Steve Chernoski, the documentarian who's tackled the mystery of the line between North and South Jersey. Drive around a bit, ask the locals which side they identify with more, and decide by acclaim.

I read a few years ago that a group of surveyors were using GPS instruments to determine the straightness of Lawrence's line. If they drove the same stretch of Province Line Road that I did, they'd be pretty impressed. Check out how straight it is:

I wish I could report that the full length of the road is as pin-straight and travels clear to Little Egg Harbor, but it's not and it doesn't. About a mile away from where I took this photo, I ran into a dead end and had to resort to an intersecting street. Looking at the map when I got home, I discovered the road makes some twists and turns before terminating near a shopping mall.

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Sue and Ivan versus the Volcano

The folks at Lusscroft Farm have been tapping the property's maple trees in preparation for a maple sugaring event held on St. Patrick's Day weekend. I only became aware of it a day or two beforehand, and I insisted that we had to make a return visit to see whether New Jersey maple syrup is better than the Vermont variety.

We'd just stumbled on the place the first time we visited, so this time I made sure we had the address plugged into the GPS. Rather than bringing us to the front gate, it took us around the side, past a surprising street sign:

A volcano? This was a new one on me. The last time I ran into a sign like this on the road, I was in Hawaii, where you're driving on literal volcanoes all the time. New Jersey, it need not be said, is not exactly known for its volcanic activity. Then again, the hill we were driving on did seem kind of different from the others we'd traversed in Sussex County.

A little bit of research revealed a little bit of information. Rutan Hill, as it's called, is, indeed, a 440 million year-old extinct volcano. Not only is it the only one in New Jersey, it's one of the two spots in the state where one can see the natural occurrence of nepheline syenite, a very rare igneous rock with origins in magma. The volcanic action also essentially baked the surrounding sedimentary rock, which we saw as we hiked around Lusscroft. A lot of the stones seemed a little grayer than what you usually see, and maybe a little more crumbly, but that might have just been my perspective.

Given the title of this entry, you're probably wondering if we went to the peak of the volcano to make a symbolic sacrifice. Well, in true Jersey fashion, the road was marked "PRIVATE -- DO NOT ENTER," and while we surmised that residents had put the sign up illegally to deter curiosity seekers, we didn't want to take any chances. And sadly, builders had already made a sacrifice we'd never dream of: they covered the apex of the hill with a house. Those attempting to get a view of a geologic wonder are left trying to imagine the volcano untouched by the hand of man.

The maple syrup quest was both interesting and disappointing. They'd sold out of syrup by the time we got there, but we got a little taste along with an education on the maple syrup process. For one thing, we learned that a grouping of tapped maple trees is called a sugarbush. And the sap gathering process isn't what we expected. Instead of gallon buckets hanging from individual taps, they use a vacuum-sealed system of flexible tubing that collects the sap and delivers it, by gravity, to a central receptacle downhill. Pretty cool!

I guess you could say that for the day, the state-by-state comparisons were a mixed bag. On volcanoes, New Jersey definitely pales in comparison to Hawaii, but to this taste tester, our maple syrup is definitely on a par with Vermont's!

We'd just stumbled on the place the first time we visited, so this time I made sure we had the address plugged into the GPS. Rather than bringing us to the front gate, it took us around the side, past a surprising street sign:

|

| Sorry for the blurriness of the photo. I guess I was so excited that my hand was shaking, plus I was using a phone camera. |

A little bit of research revealed a little bit of information. Rutan Hill, as it's called, is, indeed, a 440 million year-old extinct volcano. Not only is it the only one in New Jersey, it's one of the two spots in the state where one can see the natural occurrence of nepheline syenite, a very rare igneous rock with origins in magma. The volcanic action also essentially baked the surrounding sedimentary rock, which we saw as we hiked around Lusscroft. A lot of the stones seemed a little grayer than what you usually see, and maybe a little more crumbly, but that might have just been my perspective.

Given the title of this entry, you're probably wondering if we went to the peak of the volcano to make a symbolic sacrifice. Well, in true Jersey fashion, the road was marked "PRIVATE -- DO NOT ENTER," and while we surmised that residents had put the sign up illegally to deter curiosity seekers, we didn't want to take any chances. And sadly, builders had already made a sacrifice we'd never dream of: they covered the apex of the hill with a house. Those attempting to get a view of a geologic wonder are left trying to imagine the volcano untouched by the hand of man.

The maple syrup quest was both interesting and disappointing. They'd sold out of syrup by the time we got there, but we got a little taste along with an education on the maple syrup process. For one thing, we learned that a grouping of tapped maple trees is called a sugarbush. And the sap gathering process isn't what we expected. Instead of gallon buckets hanging from individual taps, they use a vacuum-sealed system of flexible tubing that collects the sap and delivers it, by gravity, to a central receptacle downhill. Pretty cool!

I guess you could say that for the day, the state-by-state comparisons were a mixed bag. On volcanoes, New Jersey definitely pales in comparison to Hawaii, but to this taste tester, our maple syrup is definitely on a par with Vermont's!

Saturday, March 17, 2012

The Luck of the Irish at Ellis Island

A while back I noted that the lion's share of Ellis Island is, in fact, in New Jersey. The man-made South Side of the island was constructed to house the immigrant hospital where tens of thousands of recent arrivals were nursed to health in anticipation of their eventual admission to the United States.

Mentioning Ellis Island usually raises thoughts of those immigrants' travails, but as a volunteer for the National Park Service and its non-profit partner Save Ellis Island, I share the story of the hospital's dedicated staff of Public Health Service physicians and nurses. It wasn't until I started researching the women doctors who practiced there that I found an instance where the two intersected: a child of immigrants who showed how quickly American families can rise from humble immigrant roots to make a positive impact on our country.

Rose Cecilia Faughnan was born on August 23, 1873 in Newark, the daughter of Irish immigrants, Timothy Faughnan and Mary Farley Faughnan. While the year of her mother's crossing is unclear from census records, her father came to the United States as a young boy in 1847. It's pretty safe to assume that both sets of Rose's grandparents were protecting their children from the devastation of the potato famine ravaging the country in the late 1840s.

The Faughnans had five other children besides Rose: Timothy, John, Elizabeth, Marie and Anna. By 1900, Mary had died and apparently the 27 year old Rose remained in the household to care for her siblings and father. Ten years later, she's listed on the census as a medical student, but she wasn't the only one with ambitions. Her brother John is listed as a law student, her brother Timothy as a dentist, and sister Anna as a teacher. Clearly, they'd been encouraged in their studies and prompted to do the most they could with their intelligence and capitalize on every opportunity.

By 1914, Rose had earned her degree from the Medical College of Baltimore and was the second female doctor to practice at the Public Health Service (PHS) hospital on Ellis Island. Private sector employment was still difficult for women physicians to secure, but the PHS understood their value in an environment where many female immigrants were both suspicious and fearful of men. The doctors at Ellis were required to wear uniforms, an intimidating sight for people who didn't speak English and may have been escaping persecution from the military in their home countries. Dr. Faughnan and her fellow women doctors (up to four by 1924) were a calming influence and could perform the sometimes invasive examinations that were necessary to determine immigrant patients' medical status.

After leaving the PHS and Ellis Island, Dr. Faughnan served the Newark Public Schools and St. James Hospital in the Ironbound. She died of pneumonia and bladder cancer on March 26, 1947, having made a positive impact on thousands of people during her medical career. It's a safe assumption that many Americans wouldn't be here today had she not diagnosed, treated and cured their immigrant forebears.

I was reminded of Dr. Faughnan and her parents after reading an essay written by a more recent immigrant. Barry O'Donovan noted that while the Irish have been beset by some devastatingly bad circumstances over the centuries, there are those who turn misfortune into success through hard work and persistence. The luck of the Irish, it seems, isn't so much lucky as it is well earned.

Mentioning Ellis Island usually raises thoughts of those immigrants' travails, but as a volunteer for the National Park Service and its non-profit partner Save Ellis Island, I share the story of the hospital's dedicated staff of Public Health Service physicians and nurses. It wasn't until I started researching the women doctors who practiced there that I found an instance where the two intersected: a child of immigrants who showed how quickly American families can rise from humble immigrant roots to make a positive impact on our country.

|

| Dr. Rose Faughnan in a 1922 passport application photo. |

The Faughnans had five other children besides Rose: Timothy, John, Elizabeth, Marie and Anna. By 1900, Mary had died and apparently the 27 year old Rose remained in the household to care for her siblings and father. Ten years later, she's listed on the census as a medical student, but she wasn't the only one with ambitions. Her brother John is listed as a law student, her brother Timothy as a dentist, and sister Anna as a teacher. Clearly, they'd been encouraged in their studies and prompted to do the most they could with their intelligence and capitalize on every opportunity.

By 1914, Rose had earned her degree from the Medical College of Baltimore and was the second female doctor to practice at the Public Health Service (PHS) hospital on Ellis Island. Private sector employment was still difficult for women physicians to secure, but the PHS understood their value in an environment where many female immigrants were both suspicious and fearful of men. The doctors at Ellis were required to wear uniforms, an intimidating sight for people who didn't speak English and may have been escaping persecution from the military in their home countries. Dr. Faughnan and her fellow women doctors (up to four by 1924) were a calming influence and could perform the sometimes invasive examinations that were necessary to determine immigrant patients' medical status.

After leaving the PHS and Ellis Island, Dr. Faughnan served the Newark Public Schools and St. James Hospital in the Ironbound. She died of pneumonia and bladder cancer on March 26, 1947, having made a positive impact on thousands of people during her medical career. It's a safe assumption that many Americans wouldn't be here today had she not diagnosed, treated and cured their immigrant forebears.

I was reminded of Dr. Faughnan and her parents after reading an essay written by a more recent immigrant. Barry O'Donovan noted that while the Irish have been beset by some devastatingly bad circumstances over the centuries, there are those who turn misfortune into success through hard work and persistence. The luck of the Irish, it seems, isn't so much lucky as it is well earned.

Wednesday, March 14, 2012

Stuff that's not there anymore: Communipaw Cove

Go to Liberty

State Park Jersey

City terminal of the Central Railroad of New Jersey stands restored

against the Hudson River , its rail shed a

small indication of the massive amounts of people and freight that once entered

and departed the area. If you look carefully around the edges of the lawns and

access roads, you’ll see another indication of previous use: the warning signs

showing where nature is being allowed to remediate soil polluted by the

industry that once stood there.

Aerial photographs of the area from the 1940s and 50s show a

substantial number of docks where freight would be loaded onto or off ships. It

was in the southernmost part of this area, at Black Tom Wharf not far from the Statue of Liberty,

that an act of sabotage in 1916 helped prompt the United States

The area’s status as a shipping center actually began with

the construction of the Morris

Canal Jersey City shore of the Hudson River, the

canal brought Pennsylvania coal east and New Jersey New York City

The canal’s builders would have seen a much different

topography than we do today. Instead of an expanse of land to the south, they’d

have seen a naturally scooped-out shoreline. That was Communipaw Cove, the

summer home of Native Americans before the arrival of the Dutch in the 1630s. A

tidal flatlands, the area was rife with oysters, as was much of New York Harbor

Once the Dutch West Indies Company planted itself there,

industrialization, as it was at the time, started in earnest. Settlements sprouted

up in the area, including plantations powered by slave labor. Then, as now,

proximity to Lower Manhattan fueled

transportation: regulated ferry service was established between the island and

Communipaw in 1669. Apparently Jersey

City

But why does the cove no longer exist? Well, it comes back,

in some regards, to the Morris

Canal Phillipsburg and Jersey City Pennsylvania coal, LVRR wanted to

beef up its New Jersey capacity to get to the

lucrative New York City New York Liberty

State Park

A fair amount of coastal northern New Jersey Liberty State Park

Monday, March 12, 2012

Need true north? You might find it at your county seat.

In front of the old Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington, two curious granite obelisks stand, with thick oxidized metallic disks atop them. They're about 100 feet apart, and the one closer to the street corner bears a shield with the words "True Meridian 1883."

Ivan and I came upon these curious markers last month. They bear no explanation, no historical markers, and until we found the shield, we thought they might be fancy hitching posts for wagons. On further examination, and noticing the arrow etched on the top of one of the metallic discs, we knew these were utilitarian objects of a different sort.

Put together the location (the county seat) and the geographic term (meridian), and you could surmise that the obelisks have something to do with surveying, measurement or standards setting. You'd be absolutely right. After I got home, I did a little research and luckily found the story of how and why these markers came to be.

Before the days of global positioning satellites, surveyors counted on a number of mechanical instruments to find true north, and, by extension, property boundaries and mapped points. Trouble was, true north by their instruments wasn't always true north. Compasses can be compromised by other magnetic points in the Earth, and they're not all calibrated properly. Thus, measurements could vary from surveyor to surveyor, and they could even change from year to year. Coming to a commonly agreed-upon perpetual calibration standard for true north would go a long way toward clearing any confusion among land owners.

Inconsistencies like these were apparently frequent and troubling enough for the New Jersey State Legislature to act on a solution. In 1863 they deemed that a pair of true meridian markers be set at each county courthouse in the state, providing an easily-found tool for surveyors to regularly check the accuracy of their compasses. By law, every surveyor was required to set up his equipment on the meridian obelisk and record the magnetic declination readings at the county courthouse. (For those of us who didn't major in geography, magnetic declination is the difference between true north ("top" of the earth's axis) and magnetic north (the direction a compass needle points). I'd figure that having the measurement standard right there would prevent any monkeying around, as the heavy, immovably-placed markers were impervious to theft and vandalism.

The thing I find amazing is that they got the standard setting right. Back in the day, surveyors used celestial observation to set 'north,' which apparently took some time and calculation. The law required the county meridians to be set within one minute -- a sixtieth of a degree -- of true north. My GPS is on the blink and I don't have any other navigational devices, so I wasn't able to test the accuracy of the Flemington markers, but I have to believe they're true.

March 18 starts National Surveyors Week, so it's possible you might find some interesting events at or near any of the county true meridians. Stop by an old county courthouse to find out, and even if you don't find a surveyor, take a moment to face true north.

Ivan and I came upon these curious markers last month. They bear no explanation, no historical markers, and until we found the shield, we thought they might be fancy hitching posts for wagons. On further examination, and noticing the arrow etched on the top of one of the metallic discs, we knew these were utilitarian objects of a different sort.

Put together the location (the county seat) and the geographic term (meridian), and you could surmise that the obelisks have something to do with surveying, measurement or standards setting. You'd be absolutely right. After I got home, I did a little research and luckily found the story of how and why these markers came to be.

Before the days of global positioning satellites, surveyors counted on a number of mechanical instruments to find true north, and, by extension, property boundaries and mapped points. Trouble was, true north by their instruments wasn't always true north. Compasses can be compromised by other magnetic points in the Earth, and they're not all calibrated properly. Thus, measurements could vary from surveyor to surveyor, and they could even change from year to year. Coming to a commonly agreed-upon perpetual calibration standard for true north would go a long way toward clearing any confusion among land owners.

Inconsistencies like these were apparently frequent and troubling enough for the New Jersey State Legislature to act on a solution. In 1863 they deemed that a pair of true meridian markers be set at each county courthouse in the state, providing an easily-found tool for surveyors to regularly check the accuracy of their compasses. By law, every surveyor was required to set up his equipment on the meridian obelisk and record the magnetic declination readings at the county courthouse. (For those of us who didn't major in geography, magnetic declination is the difference between true north ("top" of the earth's axis) and magnetic north (the direction a compass needle points). I'd figure that having the measurement standard right there would prevent any monkeying around, as the heavy, immovably-placed markers were impervious to theft and vandalism.

The thing I find amazing is that they got the standard setting right. Back in the day, surveyors used celestial observation to set 'north,' which apparently took some time and calculation. The law required the county meridians to be set within one minute -- a sixtieth of a degree -- of true north. My GPS is on the blink and I don't have any other navigational devices, so I wasn't able to test the accuracy of the Flemington markers, but I have to believe they're true.

March 18 starts National Surveyors Week, so it's possible you might find some interesting events at or near any of the county true meridians. Stop by an old county courthouse to find out, and even if you don't find a surveyor, take a moment to face true north.

Saturday, March 10, 2012

Crossing the Black Cat's path in Absecon

If you grew up near a highway in New Jersey any time before the early 1980s, you probably remember at least one piece of interesting roadside architecture. My formative years were spent in Union, so I got an eyeful of Route 22 wonders like the Flagship and the Leaning Tower of Pizza.

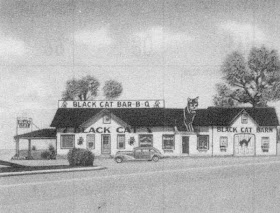

You can imagine my eagerness, then, to follow up on an e-mail that came into the Hidden New Jersey mailbox last month. A new reader told me about a roadside tavern in Absecon, a few miles south of one of our regular stops, Forsythe NWR. It's a can't miss because there's a big black cat on the roof.

The Black Cat Bar & Grill has been a landmark on the White Horse Pike for generations, offering food, libations and a navigational aid to travelers on their way to and from Atlantic City. As the story goes, it's the oldest business in Absecon and was originally marked by a huge black cat sign with a blinking green eye. My source told me that as a result of Lady Bird Johnson's highway beautification efforts, the larger, operational feline was taken down in favor of a smaller one, though people still ask the owner to restore the blinker.

Using a beautiful-day visit to Forsythe as an excuse for a Route 9 jaunt, I went the extra couple of miles to the White Horse Pike to check out the Cat. The place itself is on an intersection, as all good roadhouses should be, and I had to switch directions to hit it as it should be seen -- from the east with Atlantic City at one's back. I could see why the blinking eye might have been considered a distraction: it's a good sized intersection, and from a certain angle, a driver might take the pulsating green as a signal instead of the installed traffic light.

The building has clearly been updated, but the exterior still exudes a bit of a roadhouse look, including a big sign advertising package goods. "Welcome to Absecon," it said on the bottom, "home of nice people." Well, heck, how can I resist that?

The friendly people part was clear as I walked in and was welcomed by one of the bartenders. Rather than sitting at the bar, I grabbed a nearby booth and checked out the extensive menu. It included a few cat-named dishes as well as a healthy amount of seafood and burger options -- maybe about as extensive as a smaller diner, but without the breakfast choices. I went for a bacon cheeseburger with the California-style works and then took a subtle look around the place. A complete package goods store is set up not far from the bar area, and a more restaurant-y room is at the opposite end. Personally, when I travel alone I tend not to frequent bars, even for lunch, but this felt really neighborly. My biggest problem with the place was what they had on the TV: a Phillies spring training game. Being that I was indisputably in South Jersey, though, I couldn't complain, nor would I have. No sense in testing the boundaries of the Abseconites' friendliness, right? Instead, I quietly enjoyed their two-run deficit.

Any hint of 'rare' was cooked out of the burger, bacon included, but it was both tasty and held together well within the kaiser roll. I really liked the fries -- pleasantly crisp on the outside and just well done enough on the inside. When I bring Ivan the next time, I'm going to try out some of the seafood, maybe the oyster po boy or the crab balls.

Further research says that until about 15 years ago, the Black Cat was a classic shot-and-a-beer kind of place, without food. The public's changing drinking habits prompted ownership to add the dining options, opening up a whole new market. I'd feel comfortable bringing my mom there for a satisfying lunch, and, in fact, an older woman a few tables away from me was enjoying her meal and a conversation with one of the waitresses.

I think we found a new reliable for those Brigantine trips, but maybe with a slight twinge of guilt. Going to the Cat after seeing the birds might be a bit of a betrayal.

You can imagine my eagerness, then, to follow up on an e-mail that came into the Hidden New Jersey mailbox last month. A new reader told me about a roadside tavern in Absecon, a few miles south of one of our regular stops, Forsythe NWR. It's a can't miss because there's a big black cat on the roof.

|

| The Black Cat, in the day. |

Using a beautiful-day visit to Forsythe as an excuse for a Route 9 jaunt, I went the extra couple of miles to the White Horse Pike to check out the Cat. The place itself is on an intersection, as all good roadhouses should be, and I had to switch directions to hit it as it should be seen -- from the east with Atlantic City at one's back. I could see why the blinking eye might have been considered a distraction: it's a good sized intersection, and from a certain angle, a driver might take the pulsating green as a signal instead of the installed traffic light.

|

| The non-blinking cat atop the roof. |

The friendly people part was clear as I walked in and was welcomed by one of the bartenders. Rather than sitting at the bar, I grabbed a nearby booth and checked out the extensive menu. It included a few cat-named dishes as well as a healthy amount of seafood and burger options -- maybe about as extensive as a smaller diner, but without the breakfast choices. I went for a bacon cheeseburger with the California-style works and then took a subtle look around the place. A complete package goods store is set up not far from the bar area, and a more restaurant-y room is at the opposite end. Personally, when I travel alone I tend not to frequent bars, even for lunch, but this felt really neighborly. My biggest problem with the place was what they had on the TV: a Phillies spring training game. Being that I was indisputably in South Jersey, though, I couldn't complain, nor would I have. No sense in testing the boundaries of the Abseconites' friendliness, right? Instead, I quietly enjoyed their two-run deficit.

Any hint of 'rare' was cooked out of the burger, bacon included, but it was both tasty and held together well within the kaiser roll. I really liked the fries -- pleasantly crisp on the outside and just well done enough on the inside. When I bring Ivan the next time, I'm going to try out some of the seafood, maybe the oyster po boy or the crab balls.

Further research says that until about 15 years ago, the Black Cat was a classic shot-and-a-beer kind of place, without food. The public's changing drinking habits prompted ownership to add the dining options, opening up a whole new market. I'd feel comfortable bringing my mom there for a satisfying lunch, and, in fact, an older woman a few tables away from me was enjoying her meal and a conversation with one of the waitresses.

I think we found a new reliable for those Brigantine trips, but maybe with a slight twinge of guilt. Going to the Cat after seeing the birds might be a bit of a betrayal.

Wednesday, March 7, 2012

Dracula birds and abandoned batteries on Sandy Hook

Even the crummy days this winter don't seem half bad. Though it was cloudy and felt as if showers were highly possible, I made the trip to Sandy Hook the other day to check out a bayside birding spot Ivan had shown me a few weeks ago.

As we've experienced before on the Hook, he and I knew the same location for different reasons. We parked near the Nike launch site and walked north on the southbound road until we reached a driveway with a closed wooden bar gate. Vehicular traffic was banned, but this was a well established birding area. It's even on the maps the Audubon Society used to hand out at its now-closed nature center near Guardian Park.

A short walk took us to our destination, one of the best duck sighting spots on the Hook. All around, though, was the evidence of the Army's presence during World War II. The footpath was originally a road between Batteries Kingman and Mills, both built just before the United States entered the war. A few dozen feet into the bay were several wooden pilings that had once held up a munitions dock that took in supplies and explosives for the batteries. And if you knew what you were looking for, several hundred feet farther south you could see two concrete dynamite bunkers that had once been safely buried under sand. Erosion had taken its toll over the years, making it difficult to picture what the spot had looked like when active.

A short walk took us to our destination, one of the best duck sighting spots on the Hook. All around, though, was the evidence of the Army's presence during World War II. The footpath was originally a road between Batteries Kingman and Mills, both built just before the United States entered the war. A few dozen feet into the bay were several wooden pilings that had once held up a munitions dock that took in supplies and explosives for the batteries. And if you knew what you were looking for, several hundred feet farther south you could see two concrete dynamite bunkers that had once been safely buried under sand. Erosion had taken its toll over the years, making it difficult to picture what the spot had looked like when active.

Attempting to get to the bunkers and Mills will put you into restricted territory, so I didn't try that, but I did see that a few entrances to Kingman were visible from the shore. Obscured by vegetation that had taken root in the copious amounts of sand and soil that had covered its roof and walls since its abandonment, the massiveness of the battery isn't easily imagined. All of the visible entrances are well secured, and the interior is both dark and hazardous, so exploration was unadvisable.

When I returned on my own last week, I wasn't sure what I'd find, and in the case of the birds, I didn't know what I'd be able to identify. I was relieved, then, that my first glance delivered an old reliable for me: the cormorant. Ten of them, in fact, lined up like soldiers on the pilings I mentioned earlier.

When I returned on my own last week, I wasn't sure what I'd find, and in the case of the birds, I didn't know what I'd be able to identify. I was relieved, then, that my first glance delivered an old reliable for me: the cormorant. Ten of them, in fact, lined up like soldiers on the pilings I mentioned earlier.

Cormorants are very easily identified in silhouette, especially in what I call the 'Dracula' position. The bane of fishermen everywhere, corms scout the waters for good fin fish and then dive in to get them. Thing is, though, unlike most aquatic birds, their feathers aren't water repellent, so when they get out of the water, they spread their wings to air dry them. In that position, they look like good ol' Bela Lugosi in his signature role, preparing to transform himself into a bat.

Take a look and let me know what you think:

Come to think of it, that comparison gives me a bit of a shiver when I think of the proximity of the dark, damp batteries and the potential they hold for substantial bat colonies. Who knows? A hapless explorer within Kingman or Mills might find herself suddenly enveloped by a dark cape and then relieved of a few units of O Positive. Perhaps the cormorants are trying to tell us something.

Probably not, but if it acts as a deterrent, all the better.

As we've experienced before on the Hook, he and I knew the same location for different reasons. We parked near the Nike launch site and walked north on the southbound road until we reached a driveway with a closed wooden bar gate. Vehicular traffic was banned, but this was a well established birding area. It's even on the maps the Audubon Society used to hand out at its now-closed nature center near Guardian Park.

A short walk took us to our destination, one of the best duck sighting spots on the Hook. All around, though, was the evidence of the Army's presence during World War II. The footpath was originally a road between Batteries Kingman and Mills, both built just before the United States entered the war. A few dozen feet into the bay were several wooden pilings that had once held up a munitions dock that took in supplies and explosives for the batteries. And if you knew what you were looking for, several hundred feet farther south you could see two concrete dynamite bunkers that had once been safely buried under sand. Erosion had taken its toll over the years, making it difficult to picture what the spot had looked like when active.

A short walk took us to our destination, one of the best duck sighting spots on the Hook. All around, though, was the evidence of the Army's presence during World War II. The footpath was originally a road between Batteries Kingman and Mills, both built just before the United States entered the war. A few dozen feet into the bay were several wooden pilings that had once held up a munitions dock that took in supplies and explosives for the batteries. And if you knew what you were looking for, several hundred feet farther south you could see two concrete dynamite bunkers that had once been safely buried under sand. Erosion had taken its toll over the years, making it difficult to picture what the spot had looked like when active.Attempting to get to the bunkers and Mills will put you into restricted territory, so I didn't try that, but I did see that a few entrances to Kingman were visible from the shore. Obscured by vegetation that had taken root in the copious amounts of sand and soil that had covered its roof and walls since its abandonment, the massiveness of the battery isn't easily imagined. All of the visible entrances are well secured, and the interior is both dark and hazardous, so exploration was unadvisable.

When I returned on my own last week, I wasn't sure what I'd find, and in the case of the birds, I didn't know what I'd be able to identify. I was relieved, then, that my first glance delivered an old reliable for me: the cormorant. Ten of them, in fact, lined up like soldiers on the pilings I mentioned earlier.

When I returned on my own last week, I wasn't sure what I'd find, and in the case of the birds, I didn't know what I'd be able to identify. I was relieved, then, that my first glance delivered an old reliable for me: the cormorant. Ten of them, in fact, lined up like soldiers on the pilings I mentioned earlier.Cormorants are very easily identified in silhouette, especially in what I call the 'Dracula' position. The bane of fishermen everywhere, corms scout the waters for good fin fish and then dive in to get them. Thing is, though, unlike most aquatic birds, their feathers aren't water repellent, so when they get out of the water, they spread their wings to air dry them. In that position, they look like good ol' Bela Lugosi in his signature role, preparing to transform himself into a bat.

Take a look and let me know what you think:

|

| Double Crested Cormorant - Phalacrocorax auritus |

|

| Bela Lugosi as Dracula - Vampiricus scaricus |

Probably not, but if it acts as a deterrent, all the better.

Monday, March 5, 2012

Voting 'em up or down in Newton

Wandering around Sussex County this weekend, we found ourselves driving into the center of Newton, the county seat. We didn't expect to drive almost smack dab into a relic of colonial history: the town green. Now adorned with a massive Civil War memorial and an old county office building, it's bordered on all sides by what passes for city roads in the quieter parts of the state.

When you talk about a colonial town green, New England will come to mind for a lot of people. Bring up the topic in Northern New Jersey, and many will think of Morristown, which continues to maintain its park-like green in the middle of the business district. Newton's holds a special distinction: it's the only colonial county seat in the state where a courthouse on its original site fronts a town square or public green. That's a lot of qualifiers, but it basically means that when you drive into town, you can't miss seeing the Classic Revival-style courthouse. The circa 1847 structure stands on the same site as the original courthouse which was built shortly after Newton was named Sussex County seat in 1761.

We stopped to get more information from the informative Sussex County historical marker nearby. Turns out that in addition to the usual public square uses (political discourse, corporal punishment, common pasture), the Newton square was also the public polling site.

Rather than having an anonymous balloting process for municipal contests on Election Day, Newton residents voted by where they stood, physically. Sides of the green would be designated for particular candidates, voters would stand in the area that corresponded to their choice, and a headcount would be taken. And given that the green is on a hill, you'd literally be voting up or voting down, depending on where your candidate's spot was.

Newton's population grew rapidly with the construction of factories in the area, and I gather that's what put the headcount voting practice to an end in 1858. It's hard enough keeping a few dozen people standing in a single spot. Imagine how difficult it would be to keep hundreds from milling around before the official talliers lost count.

While I personally prefer the confidentiality of the voting booth, there's value in casting one's ballots publicly, in the center of town. Everyone could see who had shown up to vote, and peer pressure could encourage the tardy or reluctant to come out and participate. Those who didn't vote yet still complained about the state of affairs could easily be identified and told to hold their peace. I can imagine that the practice was the basis for many lively discussions around town in the hours and days after Election Day.

When you talk about a colonial town green, New England will come to mind for a lot of people. Bring up the topic in Northern New Jersey, and many will think of Morristown, which continues to maintain its park-like green in the middle of the business district. Newton's holds a special distinction: it's the only colonial county seat in the state where a courthouse on its original site fronts a town square or public green. That's a lot of qualifiers, but it basically means that when you drive into town, you can't miss seeing the Classic Revival-style courthouse. The circa 1847 structure stands on the same site as the original courthouse which was built shortly after Newton was named Sussex County seat in 1761.

We stopped to get more information from the informative Sussex County historical marker nearby. Turns out that in addition to the usual public square uses (political discourse, corporal punishment, common pasture), the Newton square was also the public polling site.

Rather than having an anonymous balloting process for municipal contests on Election Day, Newton residents voted by where they stood, physically. Sides of the green would be designated for particular candidates, voters would stand in the area that corresponded to their choice, and a headcount would be taken. And given that the green is on a hill, you'd literally be voting up or voting down, depending on where your candidate's spot was.

Newton's population grew rapidly with the construction of factories in the area, and I gather that's what put the headcount voting practice to an end in 1858. It's hard enough keeping a few dozen people standing in a single spot. Imagine how difficult it would be to keep hundreds from milling around before the official talliers lost count.

While I personally prefer the confidentiality of the voting booth, there's value in casting one's ballots publicly, in the center of town. Everyone could see who had shown up to vote, and peer pressure could encourage the tardy or reluctant to come out and participate. Those who didn't vote yet still complained about the state of affairs could easily be identified and told to hold their peace. I can imagine that the practice was the basis for many lively discussions around town in the hours and days after Election Day.

Friday, March 2, 2012

Visiting Princeton in Elizabeth

If you happen to get called for jury duty in Union County, be sure to check out Princeton University while you're there. You'll be walking in the footsteps of some of our most notable early Americans.

No, they haven't moved the county courthouse. It's still in Elizabeth, the county seat. The very seeds of one of America's nine colonial colleges were originally planted there, beside the First Presbyterian Church on what's now Broad Street. A marker commemorating the spot is planted squarely on the outside wall of the parish house, site of the original school building.

Colleges at the time were vastly different than they are today; the students were younger and primarily studied for the ministry. Jonathan Dickenson, the pastor at First Presbyterian, helped establish the College of New Jersey in October 1746 as an alternative to the less enlightened religious philosophy being taught at Yale. With his death the following year, the presidency of the school shifted to the Reverend Aaron Burr, father of the more famous man with the same name. He moved the school to Newark and eventually to Princeton, whose remote location he felt would provide little distraction from his students' scholarship.

Though The College of New Jersey had a brief stay in Elizabeth, the town's educational heritage had a major impact on American independence. The Parish House I mentioned earlier was built on the site of Elizabethtown Academy, which educated Revolutionary-era notables including Alexander Hamilton and his future nemesis, the younger Aaron Burr.

Hamilton made quite an impression on attorney and future New Jersey Governor William Livingston, who invited the student to live at Liberty Hall just a few miles away. The contacts the future Treasury Secretary made through Livingston were the foundation for his future accomplishments. He even established his reputation as a ladies man by wooing one of the venerable three graces, the beautiful and coquettish Catharine Livingston.

The Academy didn't survive the war, as many students joined Hamilton and some of the faculty in joining the Continental Army. The building itself, converted to a storehouse, was burned by the British in 1780.

No, they haven't moved the county courthouse. It's still in Elizabeth, the county seat. The very seeds of one of America's nine colonial colleges were originally planted there, beside the First Presbyterian Church on what's now Broad Street. A marker commemorating the spot is planted squarely on the outside wall of the parish house, site of the original school building.

Colleges at the time were vastly different than they are today; the students were younger and primarily studied for the ministry. Jonathan Dickenson, the pastor at First Presbyterian, helped establish the College of New Jersey in October 1746 as an alternative to the less enlightened religious philosophy being taught at Yale. With his death the following year, the presidency of the school shifted to the Reverend Aaron Burr, father of the more famous man with the same name. He moved the school to Newark and eventually to Princeton, whose remote location he felt would provide little distraction from his students' scholarship.

Though The College of New Jersey had a brief stay in Elizabeth, the town's educational heritage had a major impact on American independence. The Parish House I mentioned earlier was built on the site of Elizabethtown Academy, which educated Revolutionary-era notables including Alexander Hamilton and his future nemesis, the younger Aaron Burr.

Hamilton made quite an impression on attorney and future New Jersey Governor William Livingston, who invited the student to live at Liberty Hall just a few miles away. The contacts the future Treasury Secretary made through Livingston were the foundation for his future accomplishments. He even established his reputation as a ladies man by wooing one of the venerable three graces, the beautiful and coquettish Catharine Livingston.

The Academy didn't survive the war, as many students joined Hamilton and some of the faculty in joining the Continental Army. The building itself, converted to a storehouse, was burned by the British in 1780.